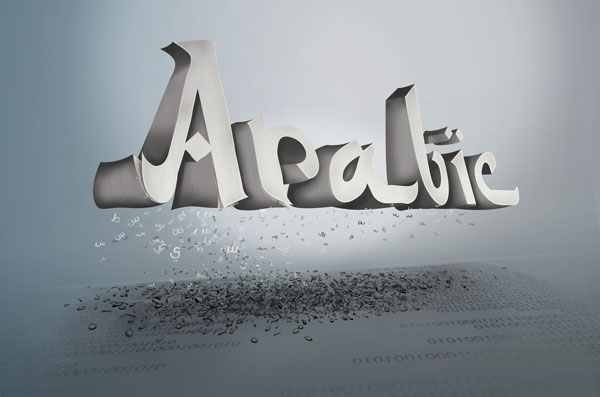

Bridging the Arabic language gap on the web

Digital content will soon supecede traditional media, this much is clear, and content creators are adapting their production methods to optimise material for online accessibility. In the middle of this global evolution to move beyond traditional media, the presence of Arabic digital content is severely lacking.

The explosion of Internet growth in the Middle East North Africa (MENA) region in the past decade has left a divide in the experience Arabic speakers can expect on the web. Internet World Stats, an organisation that tracks Internet usage puts the growth of the Arabic-speaking audience on the web at 2500 percent between the years 2000 to 2011, an impossible pace for content creators to keep up with. Arabic is the seventh most spoken language by Internet users but only three percent of digital content on the web comprises of Arabic material. However, this is changing as more people within the region realise the importance of a locally relevant web with Arabic content for them to function within.

Such significant shifts in the media landscape have inevitably resulted in noticeable changes in the means through which businesses communicate with each other and their consumers. Where radio and television were once the norm for mass marketing, businesses now use alternative media channels such as social media to reach their market.

Changing online demographics

In the MENA region people aged between 15 and 35 make up 40 percent of the population, and according to a Booz & Company report, Understanding the Arab Digital Generation, they are increasingly technologically adept with more than 80 percent using the Internet daily and 78 percent preferring Internet to traditional media such as television.

According to the report more than one-third are also unhappy with the availability of Arabic websites. While studies show online reading declining, other mediums of communication are flourishing on the Internet, 260 million videos are watched on YouTube every day in the MENA region.

Google – who bought YouTube in 2006 – recently launched Arabic Web Days, a month-long initiative in an attempt to boost Arabic web content. Maha Abouelenein, head of communications for Google in the MENA region tells The Edge that they are investing in Arabic digital content because they believe the Internet needs to be more relevant for users who speak Arabic.

Digital content, regardless of the language, requires a vast amount of time and effort to produce and keep up to date. ictQatar’s Yazen Al Safi, in charge of service enhancement and quality assurance, explains that when assessing whether to provide Arabic content, organisations take into account if the Arabic speaking audience is sizeable enough to justify investing in its creation. The changing demographics of Internet users are increasingly making it more feasible and indeed necessary. The challenge is creating unique and relevant Arabic content to meet the needs of a burgeoning Internet population.

Localising web platforms is the next step in growing Arabic content on the web. Generic translation tools available to the public are inadequate in conveying the meaning of content in a manner that is coherent to a native speaker. Taghreedat, a crowdsourcing initiative which started in Doha and now based in Abu Dhabi, uses its network of volunteers to help translate and localise popular web platforms – that is, translate the interface so that non-English speakers can use them – such as Twitter, TED, Storify and even Wikipedia.

Dr. Ahmed K. Elmagarmid, executive director of the Qatar Computing Research Institute, speaking at the Arabic Web Days Tweetup held at the Qatar National Convention Centre in December, said they are also working on improving methods to break the language barrier, and advanced programmes are in place that translate to Arabic from 26 different languages. The QCRI also has a joint initiative with Wikimedia aimed at enriching Wikipedia content in Arabic by translating and creating new material. “It is our civilisation and our material, who else can we expect to do the job?” said Dr. Elmagarmid passionately. “We must make the Arabic language a first class citizen of the web.”

Another problem facing Arabic content on the web for consolidating and indexing for search engines is the use of Arabizi, a practice that most in the field of localising are vehemently against as it creates a fracture of Arabic content. A language that developed out of necessity when Arabic alphabets were not available – it uses Latin characters and European numerals – and is extremely popular among youth in the region.

To further develop Arabic content ictQatar is working toward developing Arabic domain names and making them available to the public. “Obtaining an Arabic domain name that ends in what translates to ‘.Qatar’ is as simple as filling out a form,” Al Safi explains. This means that businesses can register their brand name to an Arabic domain and have a website made accessible purely through the use of Arabic.

A concurrence of domain names and content makes reaching their target audience much easier for Arabic-based businesses, as it eliminates any reliance upon the user’s grasp of the English language or the need for Latin characters.

Adapting content

Speaking at the Arabic Web Days event held in Doha in December 2012, Kaveh Gharib, localisation project manager for Twitter in the MENA region said the next step after localising English content is to start creating content for a global audience. Disrupting the traditional flow of information, why not then translate from Arabic to English he asked, “Do we want the global media to define who we are in the Middle East or should we take control of the flow of content and information?”

Observing the behaviour of Arabic speakers online can be very useful in understanding what type of content would be beneficial for businesses to produce. “Considering that Arabic content has been significantly gaining traction on social media sites in recent years, it is obvious that Arabic speakers are interested in a specific format of digital information,” explains Al Safi. “Interactive content such as smartphone applications and social media sites are stepping into the spotlight as the main platform for the exchange of ideas and data.”

“Instead of taking to websites to attract consumers, marketers targeting Arabic consumers should exploit their avid use of social media to their advantage,” adds Al Safi. According to Gharib there are more than 17 million tweets a day in Arabic, making one billion tweets every two months, and these numbers are continually rising.

Local start-ups

There is certainly no shortage of young entrepreneurs interested in creating Arabic digital content. What is missing, points out Al Safi, “[is] a business idea that has never been pitched before. The key to boosting the production of Arabic content is having ambitious entrepreneurs who are able to create an original idea and, more importantly, devote all their resources to materialising a functioning, profitable business from what was originally numbers and charts on a drawing board.”

Stuart Brotman, professor of communication at Northwestern University in Qatar, agrees. “There are all sorts of opportunities for pan Arabic applications, particularly because many of the applications are not in Arabic and don’t reflect the culture. I think there really are some interesting business opportunities, the questions is whether these opportunities can start in Doha and be adopted through the region.”

It is important to have an education infrastructure to support this, but not all the development needs to necessarily come from the region, Brotman adds. “India for example has a very robust application development environment but that does not mean that you cannot have individuals in Doha who are starting businesses that then utilise applications from developers around the world. Silicon Valley has done it so there is no reason that cannot be done here as well.”

Cultural preservation

Although developing Arabic content might not be of operational importance to every organisation, this is not the case with culture. There is a noticeable void where culturally relevant Arabic content is concerned. “We want to inspire users to develop content,” says Google’s Abouelenein, “and we are not just talking about translating, but in creating content. We just need to give them the tools.”

Masmoo3 for example is an Arabic audiobook portal founded by Ala Suleiman from Jordan in 2011. Telfaz11 based in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia create wildly popular web shorts on YouTube that appeal to young Arabs. An alternate approach could involve satisfying a gap in Arabic content that has yet to be catered for which is what Bylens, a stock photo production company did in Qatar, providing a locally relevant service that also documents modern Arab culture. Bearing this in mind, it may not seem imperative that Arabic content be produced when focusing on businesses but this does not hold true when taking a step back and realising that preservation of Arab culture is equally important.

The digitisation of print is essential to the rich history and culture that lies within Arabic texts. As Arabic speakers become more inclined towards the use of interactive content, there is no doubt that converting traditional text into searchable digital material is the right way to go. In relation to this, Al Safi explains that the promotion and preservation of Arabic digital content is also society’s responsibility. “In order for Arabic digital content to be seen more frequently, online society must drive its creation as a collective force,” he says, “One entrepreneur or business cannot single-handedly aim to do this but with innovation, digitisation of content, and better translation tools, Arabic speaking society can collectively push towards the creation of widely accessible Arabic digital content in its many different formats.”

Like this story? Share it.